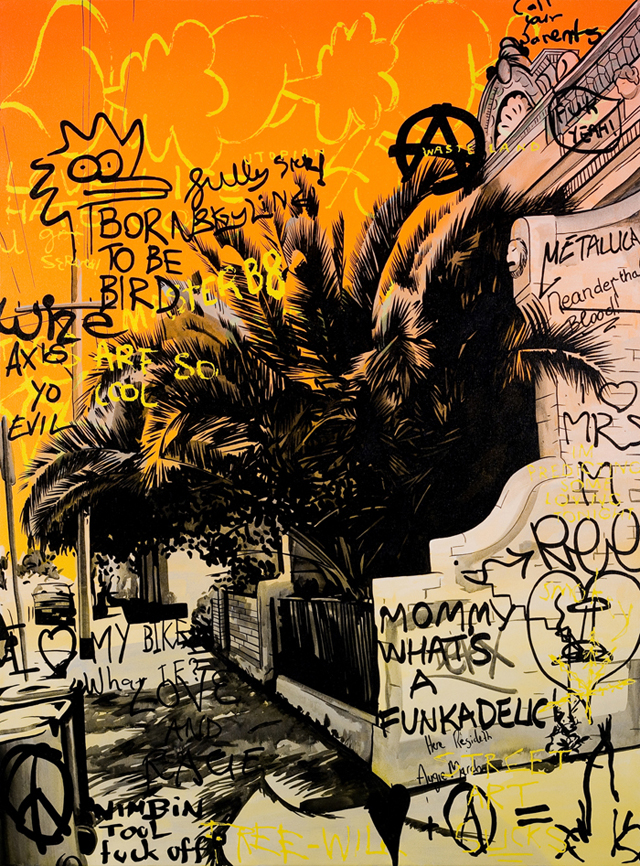

Lindberg Galleries, Melbourne, 2009

Organic automatic

Amita Kirpalani

There is violence in that font. Scratched into existence, all shout, all feeling, no clout, no divining. Dodd leaves us only indications of presence, articulated by dis-embodied voices. Those black scrawls mark out cultural, social and political specifics and we are disoriented by their optic urgency.

To write on or carve into a surface, which is not our own, represents not only a protest, but the protest of a linguistic gap. It is not the failure of verbalised speech, nor is it the failure in formally composed diatribes – it is an acute unity of feeling, gesture, action and expression. When language fails we have the gesture.

Re-etching and re-grouping these gestures, Dodd activates their ‘small dirty elements’, which are pregnant with violent meaning. Unlike protest banners – which alienate with their forceful collectiveness, these lone outcries lure us in. There is a darkness in them; a comfortable, more familiar, anarchy.

Laneways and suburban streets, particularly in Melbourne, are heavy with aerosoled expressions. These thoroughfares are not sites of contemplation, except perhaps for the savvy tourist. There is no monument here. Like there is no beauty in the ball of a foot. These laneways are sites for night-time activity. Speculations about our Post-heroic society suggest that the suburbs – not generally considered the stomping grounds of the flaneur – are a site of inquiry, intrigue and prospective violence.

Dodd points out the paradoxical mission of local councils to clear away these linguistic bursts from public buildings, alleyways and suburban fences. Commissioning graffiti removal suggests that lying underneath these little shouts, is the perfection of the original or intended surface of the built environment. These very human and immediate gestures are seen as smears on public space and architecture. But inscription can seek out a mutual fleetingness – its reception mirroring the act of stamping it out. These flourishes lurk in interstitial zones for transient interpretation and acknowledgement. Perhaps these instant editorials become reliant on being cleaned away tomorrow or next week.

We are compelled to read these text surges that Dodd presents – like their original counterparts pilfered from the alleyways, skate-parks and fences – in violent font against lurid colours. Hyperlexics have a compulsive need to read words they come across out loud. (Hyperlexica, being an advanced reading skill in children with autism or other brain damage.) Even in the average person who is not compulsive, reading is an irrepressible skill, which clouds other faculties. The Stroop test is used by many research psychologists to illustrate this; a list of words is printed with each in a different colour, but so that the colour does not correlate with the printed word – so that the word ‘Blue’ may be printed in red ink. When asked to name the colours the words are printed in, the subjects often read the words out loud instead. The theory is that ignoring the written colour name is much harder than ignoring the actual colour – even though reading is a learned skill and colour perception a basic perception.

So Dodd gives us no choice. We are implicated in these thought crimes. According to Lacan the collective subject no longer speaks but is spoken to by the symbolic structure.[1] This structure configures reality for us, it elects what counts as ‘normal’, what is accepted truth – it is the unavoidable use of the ‘they say’ at the beginning of speculative sentences that we can’t help. Dodd gives form to the conflict inherent in this call and response – he summons idyllic sunsets as backgrounds for this horizon of meaning and exchange.

The backgrounds in each of the paintings serve as a clash of textures against Dodd’s word heaps. Further compounding the insistent urgency of this found gesticulative patois, Dodd employs moments and scenes of interstice – such as the corner of a suburban street at sunset. The sunsets are at once idyllic and lurid, serving as un-peopled back-drops. It is in the sunset, in its lurid tilt towards darkness, that Dodd finds appreciation for a kind of forbidden revelry. Add to this the laneway, as a perpetually shaded site of activity – and the result is a coupling of locations of release. Similarly, novelist Christos Tsiolkas – examiner of domestic life and family truths buried in deep, dark Melbourne suburbia – suggested recently in reference to darkened forbidden places, that “darkness was the victim of a slur which equated whiteness and light with good. Shift workers, prostitutes, taxi drivers, revellers were part of the night, worlds which the day preferred to forget or ignore. [When in fact] Darkness, could be home.” [2]

Perhaps Dodd doesn’t exactly find a home for his scavenged text – since their nature dictates that they simply hover – but he finds equal fraught-ness in hyper-real colours – which both attract and repel, as an adequate analogy for his chanced-upon bursts of text.

[1] HOMER, S., 2005, Jacques Lacan, Routledge, p23.

[2] TSIOLKAS, C., 2008, Into A Liquid Ether, The Age, June 14.