Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia Project Space, 2008

24HR Art, Darwin, 2009

Darwinism & Sunset Dreaming

Mary Knights

EVIL

PANTERA + PUNK

as JOSHUA. CROCODILE WAS HERE. IN 2006[1]

Ubiquitous and utilitarian, bus shelters offer barely adequate protection from oppression, squalls and the blazing sun. Owned by everyone and no-one, within these sparse structures designated for waiting and transition strangers pause briefly. Anonymous individuals que, embark on routine journeys, vomit after drunken binges, knit pink matinee jackets, fumble and kiss, smoke cigarettes, and curl into damp newspaper seeking a brief reprieve from homelessness. Invariably lipstick stained butts, smashed beer bottles, a used condom and a fouled nappy litter the ground; chewing gum is wedged under the seat, the reek of stale urine mixes with exhaust fumes and graffiti is scrawled over the surfaces.

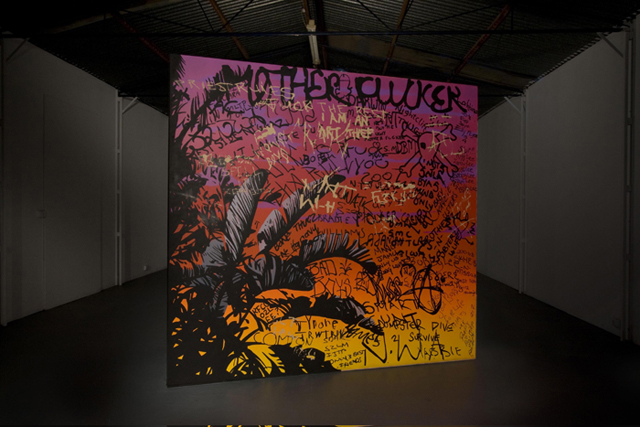

Darwinism & Sunset Dreaming was inspired by graffiti that Dodd encountered on a trip to Darwin in August 2007. The bus shelter constructed by Dodd in CACSA’s Project Space, stripped of its use as a transit-point, starkly reveals its function as a site of dialogue. Layers of imagery and text cover every visible aspect. It demands to be read and flaunts conflicting messages and disparate systems of language and codes.

Darwin was re-built quickly after Cyclone Tracey. Today it is the major regional centre in the Top End – a place of service industries, petty bureaucrats, tourists and transients. The culturally diverse and mobile population includes Chinese, Europeans, Pacific Islanders, Vietnamese, Timorese, Indonesians, Malaysians and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders from many language groups. The original owners, the Larrakia people, have a history of interaction and trading with people from across the Top End and South-East Asia, including visiting Macassan trepangers, and have maintained a complex culture and continue to accommodate other languages and incorporate cross-cultural ideas.

Despite the city’s new modern façade, lush gardens and up-beat advertising patter of a tropical multi-cultural paradise, social and economic tensions and rifts are evident. High cyclone wire fences hemming in breezy houses; a large population of homeless Aboriginal people, ‘long grasses’, camped in parks and at the fringes of the city; and explosive and declamatory graffiti hints at unrest and discontent seething barely contained just below the surface.

Continuing his on-going investigations into graffiti, Dodd took hundreds of photographs using his mobile phone. Graffiti is a language of resistance. Often the raw articulation of disenfranchised or marginalised individuals or groups. Slashing across aspirational values, graffiti is unregulated and proclaims a different order. It overtly expresses disdain for ownership and property, disregard of laws and regulations, and rejection of commodification. Offensive and defiant, refusing to conform or be silenced, it erupts in the public arena and declares realities and truths of sub-cultures operating outside of the mainstream. It defies artistic and literary conventions and develops new modes of language referencing a range of cross-cultural influences and affiliations.

Reflecting the social and cultural idiosyncrasies of the place, the content and modes of graffiti created by the young people of the Top End has some very distinctive characteristics.

Most of the text and imagery that Dodd documented was written with thick black markers, painted with aerosols or scratched into surfaces. Legible and direct, it is technically and stylistically simple. Angular capital letters, awkward cursive script and linear imagery are scribbled across bessa-brick walls, shop-front windows, street signs and tarmac. Abrupt, spontaneous gestures are inscribed into almost any surface, even the red dust covering 4WDs. The words have an aggressive power. The graffiti defies and celebrates exclusion from the mainstream.

Considering the development of contemporary youth culture in the Port Keats region, and the impact on young Indigenous people of having to grapple with their own and non-Indigenous culture, Bill Ivory, an anthropologist, recognised a strong relationship between graffiti, youth gangs and heavy metal music. Ivory noted that gangs emerged in the area in the 1980s[2] probably influenced by South Bronx and Hong Kong gang culture, Hell’s Angels and mafia shown on television and in films[3] superimposed on traditional social structures such as family and language groups.

Today around fourteen gangs exist including the Evil Warriors, Big T, Fear Factory and the Bad Boys. Ivory suggests that graffiti frequently references heavy metal and death metal bands such as Iced Earth and Iron Maidens[4] and that the location of graffiti often relates to gang or traditional territorial areas. Ivory recognised that the graffiti of the Indigenous youth from the Top End ‘does not appear to be primarily sexual or racist. It could be described as saying “This is our name, we are here, and this is our territory.”’[5]

While individuals tag their signature name, frequently the graffiti refers to belonging together.

Gang names such as ‘Judas Priest’[6] or circles of friends as in ‘Batchelor Black Bitches Rule’[7] are proclaimed explicitly revealing the significance of close-knit peer-groups and gang culture. Writing on the importance of belonging and being identified as part of a group Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) wrote of Jean Genet (1910-1986), who was immersed in gay and criminal sub-cultures in Paris: ‘For him, to be is to be identified with a group that confers the honours of the name. The progression of which occurs by formal naming, the new member of the caste possesses, within himself, the entire caste: a sailor is the entire fleet, a murderer, is all of crime. Names are titles, and “titles are sacred.”[8]

Roll-calls tag the names of gang members. In Darwin these often consist of the name of a gang EVILTERA BOYS followed by columns of initials JCMK, TGKM, RJCT, TMML…. The four initials indicate the multiple names of many of the Indigenous youth in the area, including European name, family, clan, and ceremonial group.[9] It also reveals the influences of globalisation on graffiti and the cross-cultural appropriation of style. Columns of grouped initials, usually three, is a common feature of roll-calls of some crews in America who often include K as the last initial standing for King or Kill.[10]

More intimate declarations of belonging, existence and identity; declarations of friendship, love and exclusivity are also immortalised and scratched into a physical reality.

Clara > MLTP only[11]

SDAK, SZLM, IJTP, Only 3 best friends[12]

Only us friends in Parap[13]

Some of the graffiti, especially vulgar utterances and obscenities such as ‘fuck the world’, ‘suck cock,’[14] are readily understood by most people living in Australia. Reflecting the reality that English is often not the artists’ first language, some graffiti incorporates indigenous words: NANGU CROWS EVILFUCKINWARRIOR THAT’S FUCKIN ME (word erased) 4 EVER.[15] Although intrinsically an act of defiance graffiti is often intended to be comprehensible only to peers and rivals.

RFCC O2L FE?[16](O2L = only two loves).

Like Genet’s use of argot it is deliberately hermetic and understood by only a small clique. The slang, abbreviations, coding and esoteric cultural references reinforce the exclusion and exclusivity of the sub-culture.

Genet’s character Devine, muses how each time each time he was incarcerated he searched in vain through the graffiti on the wall for words by a kindred spirit: I examine the walls for the traces of my earlier captivities, that is, of my earlier despairs, regrets, and desires that some other convict has carved out for me. I explore the surface of the walls, in quest of the fraternal trace of a friend…I await the revelation on the walls of some terrible secret…But all I have ever found has been an occasional phrase scratched on the plaster with a pin, formulas of love or revolt, more often of resignation: “Jojo of the Bastille loves his girl for life.” “My heart to my mother, my cock to the whores, my head to the hangman.”[17]

Specific cultural references, such as naming a band, are loaded with meaning. The references resonate and identify with values, style, attitude and racial politics. Ivory noted that all of the Indigenous gangs he researched identified with a Heavy Metal or Death Metal band – Evil Warriors with Iced Earth, Big T with Anthrax.[18] The sound is raw, loud, intense, aggressive and relentless, as are the lyrics, which are belligerent and engage with fighting, killing, injustice and repression, relentless pain and emotional suffering.[19] A stanza of Iron Maiden’s Sun and Steel an early Heavy Metal band goes:

Well you killed your first man at thirteen, killer instinct animal extreme

By sixteen you had learned to fight the way of the warrior

Or you took it as your right

Sunlight falling on your steel, death in life is your ordeal

Life is like a wheel.[20]

As well as being bound by hermetic language, Ivory notes that gangs often dance together in a ritualistic fashion. He describes groups waiting outside a hall until their song was played, when they would move together into the hall many wearing hoods, and walk in an anti-clockwise circle, stopping at certain points in the song and gesture as if using a microphone or guitar, before continuing to walk. [21]

JESUS IS LORD of the dance[22]

Words usually associated with Christianity appear in much of the graffiti documented by Dodd. Words that are usually have specific meanings in a religious context such as the Devil, Satanism and fear, are transformed by being integrated into graffiti. Ivory suggests the inclusion of religious words owes more to music lyrics than a specific stance against religion. Just as Genet appropriates and skews the meaning of words such as Divine, Our Lady, and Archangel, in the context of graffiti the words become highly evocative and multivalent. While not reflecting a specifically anti-Christian position they do articulate an antagonistic, pessimistic and anti-conformist stance.

Another notable aspect of the graffiti documented by Dodd, is evidence of erasure. Words, images and signs are scribbled over or violently scratched out, desecrated. Perhaps aggressively disputing another’s declaration of identity, a mark of dissent, or assertion of territorial precedence, it underlines the role of graffiti as a vibrant mode of ongoing negotiation and dialogue.

Mimicking civic signage and gaudy tourism ads that promote the idea of the Top End as a balmy holiday destination or exotic wildlife haven populated with buffalo and kangaroos, the façade of Dodd’s bus shelter is painted with a kitsch tropical sunset. Palm trees and spiky pandanus are silhouetted against a fluorescent mango-orange sky flecked with mauve clouds. Disrupting the simplistic messages and slick imagery, the surface of Dodd’s bus shelter is obliterated by a cacophony of conflicting messages, written and gouged into the surface. Although often dismissed as aberrant, the result of delinquent behaviour and of little consequence, by condensing and intensifying the graffiti, Dodd reveals the potency of graffiti developed by the complex cross-cultural sub-cultures of the Top End.

[1] Anon, documented by James Dodd, Darwin, August 2007

[2] Bill Ivory, Nemarluk to Heavy Metal, Darwin: Charles Darwin University: 2003, p. 65

[3] ibid p. 65

[4] ibid p. 65

[5] ibid p.75

[6] Anon, documented by James Dodd, Darwin, August 2007

[7] ibid

[8] Jean-Paul Sartre, Introduction, Our Lady of the Flowers, New York: Grove Press: 1987, p. 33/34

[9] Bill Ivory, Nemarluk to Heavy Metal, Darwin: Charles Darwin University: 2003, p. 75

[10] Art Crimes: The Words: Graffiti Glossary, www.graffiti.org/faq/graffiti.glossary.html, accessed 4/7/08

[11] Anon, documented by James Dodd, Darwin, August 2007

[12] ibid

[13] ibid

[14] ibid

[15] ibid

[16] ibid

[17] ibid

[18] Bill Ivory, Nemarluk to Heavy Metal, Darwin: Charles Darwin University: 2003, p. 78

[19] ibid, p. 80

[20] Sun and Steel, Iron Maiden, 1987, quoted by Bill Ivory, Nemarluk to Heavy Metal, Darwin: Charles Darwin University: 2003, p. 80

[21] Bill Ivory, Nemarluk to Heavy Metal, Darwin: Charles Darwin University: 2003, p. 83

[22] Anon, documented by James Dodd, Darwin, August 2007