Ryan Renshaw Gallery, 2009

Thinking about Darwin

Francis E. Parker

Thinking about Darwin, I confess that I think first of the man and what he represents before I think of the northern Australian city that has given James Dodd the material for his recent body of work. While evolutionary theory is still current in science, its application to art or to culture in general has come unstuck. Let me quote at length from an essay written in 1908 by the Austrian architect Adolf Loos to demonstrate why:

To us the Papuan is also amoral. The Papuan slaughters his enemies and devours them. He is no criminal. If, however, the modern man slaughters and devours somebody, he is a criminal or a degenerate. The Papuan tattoos his skin, his boat, his oar, in short, everything that is within his reach. He is no criminal. The modern man who tattoos himself is a criminal or a degenerate. There are prisons where eighty percent of the inmates bear tattoos. Those who are tattooed but are not imprisoned are latent criminals or degenerate aristocrats. If a tattooed person dies at liberty, it is only that he died a few years before he committed a murder.

The urge to ornament one’s face, and everything in one’s reach, is the origin of fine art. It is the babble of painting.(1)

I have isolated one part of Loos’s broader argument at the risk of misrepresenting him, but to summarise, he is applying evolutionary theory to culture as the basis for his argument that ‘modern man’ has attained the pinnacle of culture by doing away with ornamentation in the things that he creates – this is essentially Loos’s argument for the Modernist style. Loos speaks, however, from the privileged position of a creator of culture. He does not receive the built environment unasked for and without consultation. If one has no role in creating one’s environment the only way to render it habitable, to feel that it is one’s own, is to ‘ornament’ it. Everyone who rents a home understands this.

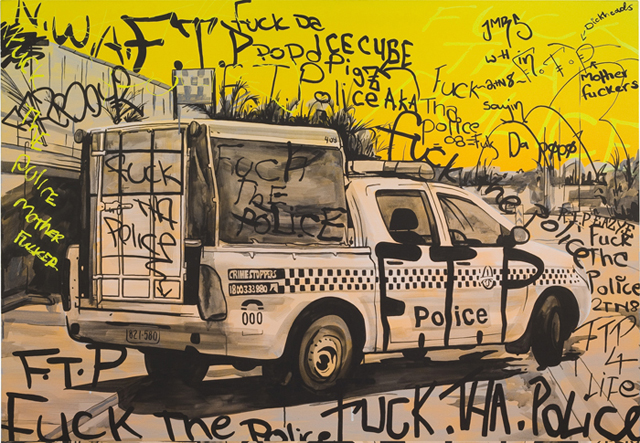

The urban wastelands where graffiti and tagging proliferate – the ‘ornamentation’ of everything within one’s reach – are, however, degenerate forms of the architectural principles that Loos and his contemporaries espoused, but they are the reality of modernity as we know it. Loos’s aspiration a century ago was that ‘Soon the streets of the cities will glow like white walls! Like Zion, the Holy City, the capital of heaven.’(2) One wonders if the town planners who rebuilt Darwin after Cyclone Tracey had something like this in mind. Loos’s modernist paradise does not match the popular concept of paradise. Paradise is promoted as a retreat from urban life into something natural and Edenic; apparently we long for our origin and not our fulfilment. Paradise inevitably also involves palm trees, like Darwin.

The modern city is filled with people who, on the one hand, are involved in the process of shaping it; legitimate citizens who at most can contribute to the cityscape or at least have a voice in the discussion around its development. On the other hand are the people who find that they can play no part in those discussions, who feel rejected by the city’s mainstream and reject it in their turn. The former can afford to flee the city when they have had enough of it and lie in the sun somewhere. Dodd has included deckchairs in this exhibition; deck chairs speak generally of leisure and specifically of ocean liners, and ocean liners were an emblem of modernity. The latter, however, cannot physically escape the city so readily and must find other means. One of them has scrawled on the fabric of the deck chairs. ‘Fucking paradise’.

We are all running away from the centre, it seems. Whether it is a holiday somewhere ‘deserted’ or the desire to be at the edge – the cutting edge – of what is happening. Mainstream culture regularly consumes that which emerges at its fringes. If one takes tattooing, for example, being as it is for Loos both ‘exotic’ and criminal, and therefore on the periphery of his world; what has become of it in our time? It no longer necessarily marks out one’s opposition to prevailing social codes but is now quite often just another expression of the bourgeois cult of the individual. The same thing has happened to stencil art. In less than a decade, Melbourne’s laneways, in which ignited the efflorescence of stencil art in Australia, have become the legitimised and publicised zones for this form of ‘ornamentation’. One cannot go into them now without finding a bridal party posing for an ‘edgy’ memento of their passage into one of society’s most conservative institutions. Stencil art and graffiti used to sit on the periphery of society but the mainstream constantly gnaws at its own banks and has picked it up and, like rock and roll, punk, fetish wear, rap or techno before it, carried it away and diluted it.

The gangs of Darwin youths, whose tagging Dodd reproduces in his paintings, find an escape in music, particularly in heavy and death metal. Or perhaps it is more that they find a social bond in the music and in leaving tags that reinforce their group identities outside the mainstream. Forming their own social structures and codes is their resort from having been left out of those of the broader population. Aggressive music and aggressive mark-making of these kinds have more resolutely held onto their marginalised positions; they are not so easy to render chic and desirable. Perhaps that is what draws these youths to identify with bands that came to prominence before they were born. This music has retained its integrity as an outsider style where others have been diffused and has so retained something that the gangs can respect; they hear in it something that reflects their position in the world.

While Dodd refers in his own writings to anthropological studies of the Darwin gangs and their allegiances to heavy metal bands, and how this is reflected in their tagging, he has not made of them Noble Degenerates – idealised or fetishised figures of revolt. He is not crusading through his art to have these youths reformed, nor is he building museum dioramas to place them into. His admiration for the distinctiveness of their tagging does not spring from an objectification of its makers; rather it is his own subjective response to finding in it a shared passion. The gangs’ peculiar adherence to heavy metal recalls his embrace of the same music during his own adolescence.

James Dodd carefully copies the tags he finds in Darwin onto his own paintings to bring their babble, their makers’ voices, into his own fine art practice. The originals remain where they are and go on proliferating while their facsimiles adorn the galleries where Dodd exhibits. His work makes one consider where the tagging comes from; not what its particular meanings might be so much as what it means as a form of expression. One weighs up this Darwin against the sunsets the colour of surf wear and the palm trees – Darwin as an earthly paradise.

1. Loos, Adolf. ‘Crime and Ornament’ 1908, republished in Miller, Bernie & Ward, Melony (eds.), Crime and Ornament, The Arts and Popular Culture in the Shadow of Adolf Loos, XYZ Books, Toronto, 2002, p.29.

2. Ibid. p.30.